Categories > Guides and Tips

Canada’s Homelessness Crisis: Key Facts and Data

- Key Insights

- Overview of Homelessness in Canada

- Defining Homelessness in Canada

- Types of Homelessness

- Duration of Homelessness

- A Brief History of Homelessness in Canada

- Key Statistics on Homelessness

- Demographic Insights

- Genders

- Age Groups

- Indigenous Peoples

- Veterans

- Immigrants, Refugees, and Visa Holders

- Causes of Homelessness in Canada

- Regional Differences in Homelessness

- Government and Community Responses

- National Housing Strategy (NHS)

- Reaching Home

- Canada’s Housing Plan

- Solutions and Innovations

- Impact of COVID-19 on Homelessness

- Future Trends and Predictions

- Reference

Key Insights

| Homelessness wasn’t an issue in Canada before the 1980s, as per the Canadian Observatory of Homelessness, but decades-long changes in federal government policies and funding transformed the country’s housing situation for the worse. In 2022, around 40,000 people across 72 communities in Canada experienced homelessness, according to Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada’s Point-in-Time count. The 2023 National Shelter Study noted that adult men between ages 25–49 years old are the most common occupants of emergency homeless shelters. Only 30% of occupants were women. There’s a strong indication that the number of homeless persons is largest in the urbanized provinces of Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec, due to these areas having the highest number of emergency shelters and beds in 2023. |

Overview of Homelessness in Canada

Defining Homelessness in Canada

The Canadian definition of homelessness was coined by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (COH) in 2017 and is the one followed by the government.

According to the COH, homelessness is:

“…the situation of an individual, family or community, without stable, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it.”

Types of Homelessness

Homelessness in itself is further classified by the COH into four major categories, based on physical living conditions:

- Unsheltered – The case where a person might be living on the streets or in places with conditions unsuitable for living.

- Emergency sheltered – A person falls under this category when they’re living in inherently temporary accommodations, like homeless, domestic violence, or disaster shelters.

- Provisionally accommodated – These include those who are staying in transitional housing (coming from an emergency shelter), ‘couch surfing’ on other people’s homes, or staying in motels for an extended period.

- At risk of homelessness – These are individuals who may face homelessness right after an unexpected crisis, expense, or event. They include those who have unstable employment or whose income can barely cover living essentials.

Duration of Homelessness

Homelessness can also be classified based on the duration, or how long a person has been experiencing it.

The Ministry of Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada (HICC, formerly Infrastructure Canada) defines homelessness as chronic if it’s experienced long-term (continuously for six months in a year) or repeatedly (at least a cumulative of 18 months in the last three years).

People who were institutionalized aren’t considered chronically homeless.

A Brief History of Homelessness in Canada

Homelessness was not a mass social issue in Canada before 1980, according to the COH Report on the State of Homelessness in 2016.

The number of people without a roof over their heads pre-1980 was very small and typically consisted of single, chronically homeless men.

Research from the same report cites the government’s move to reduce spending on affordable housing and other social and health programs throughout the 1980s as one cause of the increasing number of homeless people throughout the past decades.

Another factor noted was the negative effect of the swift decline in the number of full-time, well-paying jobs in the economy during the same period on the Canadian population’s ability to earn enough money to have a permanent home.

Today, homelessness is a key social issue because of the sheer number of individuals affected by it in the country.

Key Statistics on Homelessness

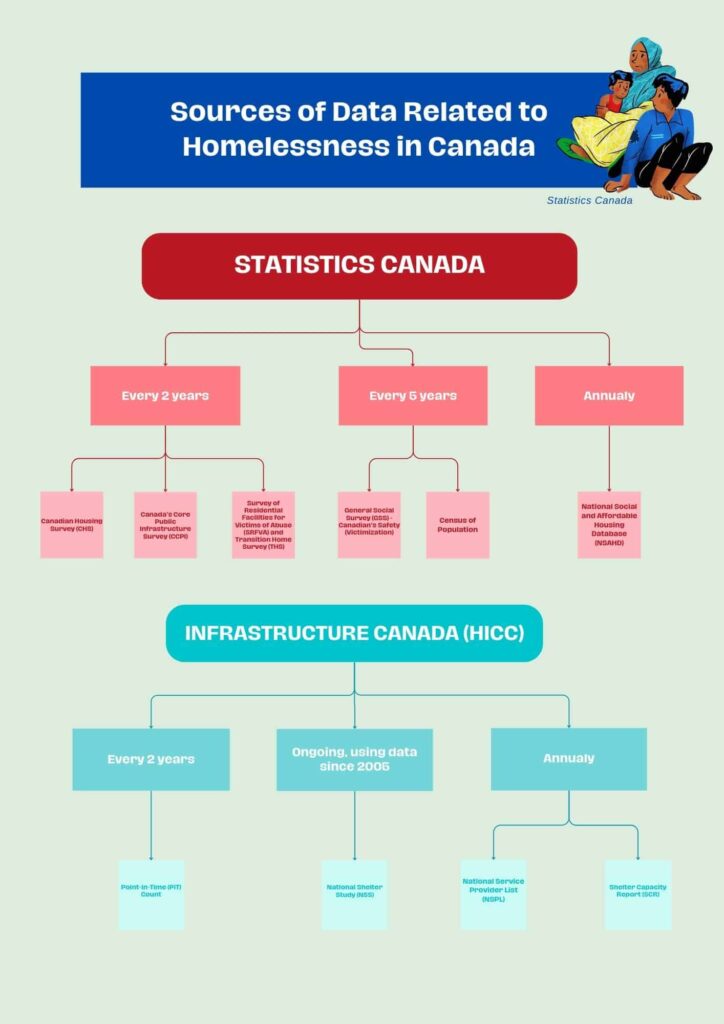

Getting the exact numbers on the number of homeless people in Canada is inherently difficult.

No single survey can give the clearest picture of homelessness in the country.

It is virtually impossible to count every single homeless person, including those who are living outside of emergency shelters (i.e., those sleeping on public property, in uninhabitable conditions, or ‘tent cities’, etc.) and the hidden homeless.

However, the conduct and use of different surveys and reports from official sources like Statistics Canada and the HICC help shed light on the different aspects of this issue.

That said, there were a lot of important findings related to homelessness in Canada in recent years.

According to the COH’s State of Homelessness in Canada Report for 2014, there are at least 235,000 people experiencing homelessness in Canada per year.

As per the HICC’s 2020-2022 PiT count, over 40,000 persons in 72 communities and regions across Canada experience homelessness. The number of people experiencing homelessness increased by 20% in the last 5 years.

32,660 people have experienced chronic homelessness in 2023, which reflects a 4.4% increase from 2022’s figure, according to the latest data from the National Shelter Study.

The same study found that in 2023, there are 561 emergency shelters with 20,864 beds all across Canada. Ontario has the most number of shelters (174) and beds (8,539).

Demographic Insights

Genders

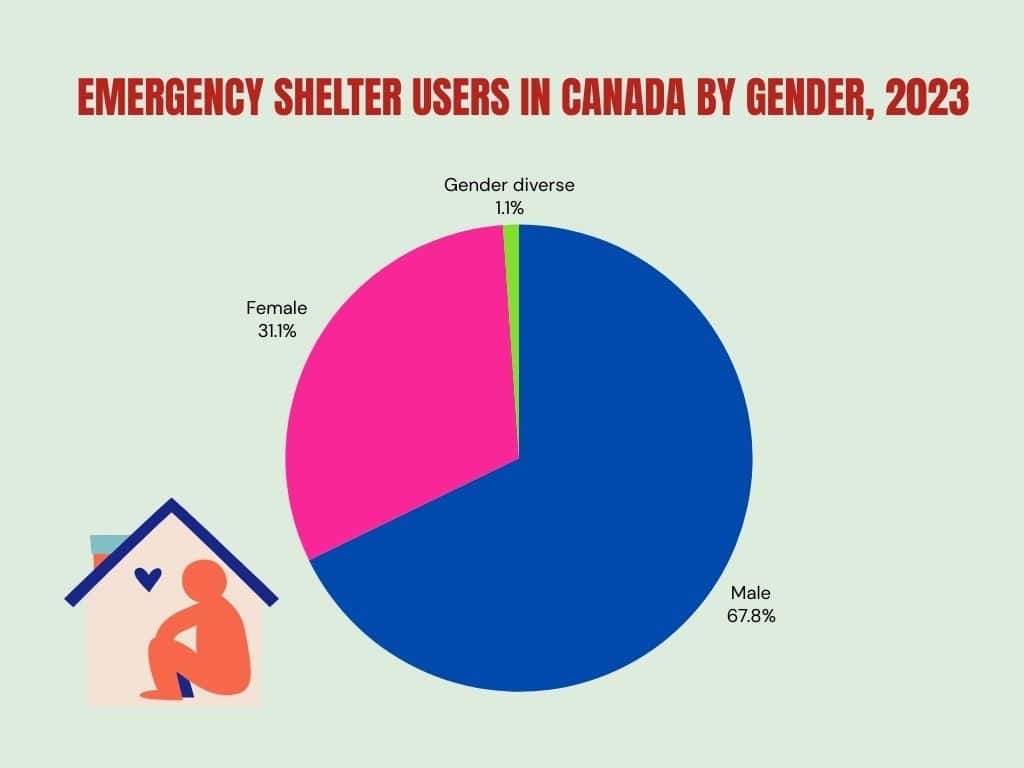

Males are more likely to experience homelessness (in general) and chronic homelessness, compared to women and other genders.

According to the 2023 National Shelter Study, around 70% of those who occupied emergency shelters that year were men, while around 30% were women, regardless of citizenship or ethnicity. It follows a consistent trend from 2015.

Another observation from the aforementioned study is the increase in the number of homeless individuals who identify as other than male or female (i.e., the 2SLGBTQI+). From just 0.5% of the total homeless population in 2015, numbers went up to 1.1% in 2021.

Age Groups

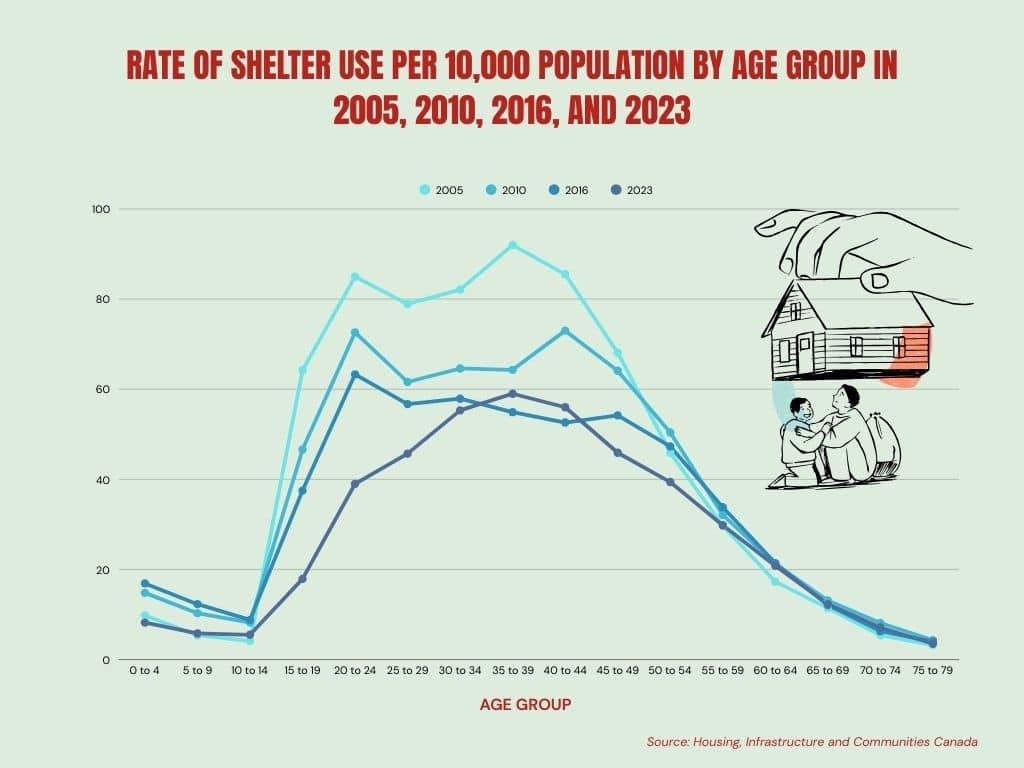

As for age groups, the National Shelter Studies from 2005 until 2023 show a consistent trend in those who are seeking emergency shelter, as seen in the chart above.

The biggest chunk of people who stayed at emergency shelters nationwide (61.3% in 2023) comprised adults aged 25 to 49 years, with the average shelter user being 39.3 years old.

There’s also an alarming rise in homelessness among Canadian youth aged 13 to 24 years old. The 2023 Shelter Capacity Report noted a 29% increase in the number of emergency shelter beds used by this age group across the country from 2022 to 2023.

Indigenous Peoples

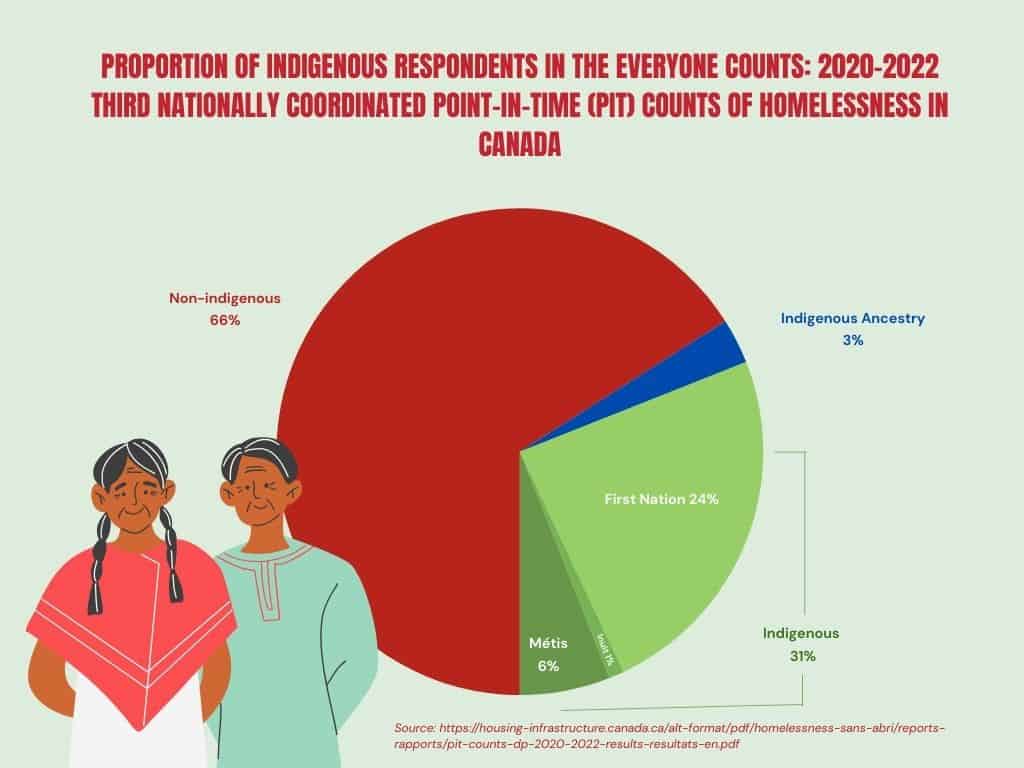

The proportion of homeless Indigenous people in Canada, in a general sense, is also a pressing concern.

Although they make up only about 5% of the Canadian population as of 2022, the Indigenous made up 31.2% of those who sought emergency shelter in 2023, as per the National Shelter Study that same year.

The 2020-2022 National Point-in-Time homeless count supports the 2023 National Shelter Study with a snapshot of the actual numbers in one night, all across Canada. As seen on the chart above, out of the 31% Indigenous respondents, 24% were First Nations, 6% Métis, and 2% Inuit.

The indigenous definition of homelessness is more nuanced and encompasses a total of 12 dimensions (including spiritual, mental, and cultural aspects), aside from the physical lack of shelter. However, there is limited, if any, quantitative information that entirely covers it.

Veterans

Veterans, or those who have rendered military service in their lifetime, comprised an average of 1-2% of the homeless shelter population in Canada, with the general trend going downwards from 2015 to 2023.

Immigrants, Refugees, and Visa Holders

For citizenship, a vast majority (around 90% from 2015 to 2023) of Canada’s homeless are Canadian citizens. Only 3% of homeless shelter users in 2023 were immigrants or permanent residents.

Although refugees, on average, comprised less than 15% of the total number of those who sought emergency shelter for homelessness since 2015, their numbers noticeably increased between 2022 and 2023 from 2% to 5.1%.

This jump is strongly linked to the increase in asylum claims after the lifting of pandemic travel restrictions.

Visa holders shared a similar trajectory at the same period, increasing their numbers from 0.5% to 0.8%.

Causes of Homelessness in Canada

There are a handful of factors that can cause or contribute to a person’s state of homelessness. Here’s a collated list of the most common causes, as per data from Statistics Canada, HICC, and COH:

- Poverty or Insufficient income – The lack of enough money to afford appropriate and permanent housing is the most common reason for homelessness among adults, until senior-aged people (aged 25 years old and above).

- Substance use – The use and subsequent addiction to illicit substances can cost a person their livelihood and finances, strain familial relationships, and even lead to incarceration.

- Conflict with a spouse or partner – People (mostly women) in domestic violence situations are most likely to seek emergency shelter with their dependent children in tow.

- Conflict with a parent or guardian – Youth and members of the 2SLGBTQI+ are at risk of becoming homeless if exposed to parental abuse or conflicts.

- Conflict with other people – Most notable for those who are in a state of hidden homelessness (e.g., people who ‘couch-surf’ or stay with people who aren’t family), the fallout of these types of setups, because of conflict, can lead to chronic homelessness.

- Mental health issues – Problems in one’s mental health can also hinder a person from maintaining their job, finances, and social relationships, ultimately leading to homelessness.

- Unsafe housing conditions – People who have been victims of natural disasters, civil unrest, and other forces outside their control have lost their homes in a snap and direly need emergency shelter.

- System failures – Vulnerable members of the population (e.g., those leaving child welfare programs, corrections facilities, or health institutions) can become homeless without adequate government and social support.

- Relocation – Tenants who got evicted or people simply having their relocation plans fall through (for a multitude of reasons) can also become homeless, specifically ‘hidden’ ones (e.g., staying with friends, extended family, or motels).

Regional Differences in Homelessness

| Number of Emergency Shelters and Beds by Province and Territory, 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Province and Territory | Total shelters | Total beds |

| Ontario | 174 | 8,539 |

| British Columbia | 128 | 3,991 |

| Quebec | 119 | 2,735 |

| Alberta | 34 | 2,878 |

| Saskatchewan | 29 | 608 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 17 | 215 |

| Nova Scotia | 15 | 698 |

| Manitoba | 15 | 608 |

| New Brunswick | 12 | 307 |

| Prince Edward Island | 6 | 85 |

| Nunavut | 6 | 93 |

| Yukon | 3 | 40 |

| Northwest Territories | 3 | 67 |

Most instances of homelessness are reported in urban areas.

The table above of shelter data across Canada shows that the largest number of emergency shelters and beds in 2023 were in the provinces of Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec. These are largely urbanized areas with notable cities like Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal.

Although homeless shelters are present in other provinces (even the rural ones like Saskatchewan, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, or Manitoba), urban figures still dwarf the rural number of these structures.

Government and Community Responses

National Housing Strategy (NHS)

The National Housing Strategy was launched in 2017 as a federal government investment project towards giving Canadians “access to safe, affordable, and inclusive housing.” It will last for 10 years, with $115+ Bn in funding.

Its key initiatives, among others, include:

- Construction and maintenance of affordable housing units,

- Creation of new housing initiatives and sustenance of existing ones, and

- Funding for specific marginalized groups affected by homelessness (e.g., indigenous peoples, women, etc.)

Reaching Home

Reaching Home, another initiative by the Canadian federal government, was launched in 2019. It builds upon the prior homelessness strategies used in the NHS.

This is a community-based program wherein the federal government partners with different local government and non-government entities in communities (urban or rural, indigenous, provincial or territorial, and even the most remote ones).

Reaching Home is an enhanced program with a more direct approach to the government’s funding and implementation of activities, data gathering, and other homelessness alleviation undertakings.

Canada’s Housing Plan

In 2024, the country’s federal government launched Canada’s Housing Plan—the latest (as of this writing) initiative for “making housing more attainable and affordable for Canadians.” It also builds upon its predecessor programs for solutions to the immense housing crisis.

In a nutshell, the Plan has three fundamental goals:

- To build more homes for the Canadian populace,

- To make it easier for Canadians to buy or rent their own home, and

- To help those who can’t afford a home end their chronic homelessness.

Solutions and Innovations

There are a handful of solutions and innovations with the goal of ending homelessness, according to the Homeless Hub. These strategies come from many places, with some already in action in some Canadian cities—two are further explained below.

The Housing First approach towards ending homelessness originated in New York City in the 1990s. It gives a strong emphasis on providing homeless persons a proper home first, before doing any other social, medical, or economic help.

A notable example of the Housing First approach in Canada is the efforts of the Calgary Homeless Foundation. From 2008 to 2012, the organization’s efforts towards housing the homeless led to an 11.6% decrease in the homeless population in the city.

There’s also the Family and Natural Supports approach, which leverages strengthening relations between endangered youth and their family (or other important people in their lives).

It thrives on the hope that social and emotional support from natural relations will steer youths away from homelessness. A notable example of this is the Covenant House in Toronto, which serves as the link between youths in homeless shelters and their family or friends.

Impact of COVID-19 on Homelessness

Although the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic lowered the utilization of emergency beds throughout Canada by 25.6% in 2020, there were still people who became homeless that year, mainly because of the effects of the pandemic on people’s economic status.

About 12% of the 2020-2022 PiT count respondents said that COVID-19 was the reason for their homelessness, with about half of them having lost their income for housing when the lockdowns hit.

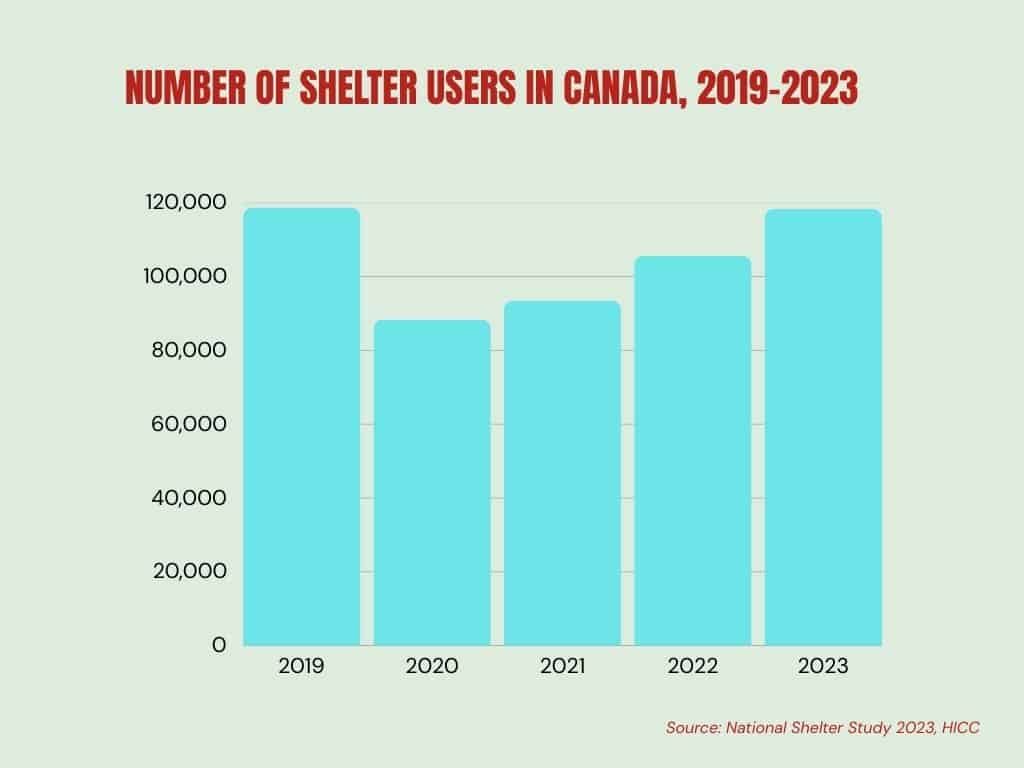

However, as seen in the chart above, the trend flipped to the other direction post-2020, with the number of people using emergency shelters climbing from 88,342 people in 2020 to 118,329 in 2023. The latest (2023) numbers are about the same as they were in 2019, pre-pandemic.

Future Trends and Predictions

Homelessness is a complex issue with its plethora of factors, but it’s undeniable how vast its impact is not just for Canadians in general, but also for at-risk and marginalized groups in society.

Unfortunately, current housing policies and programs aren’t quite effective in fighting homelessness in Canada. A study has even found that homes created under the National Housing Strategy aren’t entirely affordable to the people they were supposedly built for.

Moreover, an artificial intelligence (AI) model predicted that the homeless population in Canada could almost double by the end of the decade.

Eradicating homelessness in Canada is still a long way from being achieved, but the initiatives and efforts of the federal government and different organizations are already commendable moves towards the right direction. We just hope that these be more effective before it’s too late.

Reference

- Covenant House Toronto. (2025, February 11). Awareness, Prevention and Early Intervention. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://covenanthousetoronto.ca/our-solution/awareness-prevention-and-early-intervention/

- Dionne, M.-A., Laporte, C., Loeppky, J., & Miller, A. (2023, June 16). A review of Canadian homelessness data, 2023. Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75f0002m/75f0002m2023004-eng.htm

- Gaetz, S., Barr, C., Friesen, A., Harris, B., Hill, C., Kovacs-Burns, K., Pauly, B., Pearce, B., Turner, A., & Marsolais, A. (2012). Canadian Definition of Homelessness. HomelessHub. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from http://www.homelesshub.ca/homelessdefinition

- Gaetz, S., Dej, E., Richter, T., & Redman, M. (2016). The State of Homelessness in Canada 2016. In HomelessHub [PDF]. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC16_final_20Oct2016.pdf

- Gaetz, S., Gulliver, T., & Richter, T. (2014). The State of Homelessness in Canada 2014. In HomelessHub [PDF]. The Homeless Hub Press. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://homelesshub.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/SOHC2014.pdf

- Gaetz, S., Scott, F., & Gulliver, T. (Eds.). (2013). Housing First in Canada: Supporting Communities to End Homelessness [PDF]. Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press. https://www.homelesshub.ca//sites/default/files/HousingFirstInCanada.pdf

- HomelessHub. (n.d.-a). Family and Natural Supports | HomelessHub. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://homelesshub.ca/collection/programs-that-work/family-and-natural-supports/

- HomelessHub. (n.d.-b). Homelessness Programs that Work. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://homelesshub.ca/collection/programs-that-work/

- HomelessHub. (n.d.-c). Housing First | HomelessHub. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://homelesshub.ca/collection/programs-that-work/housing-first/

- HomelessHub. (n.d.-d). What Are the Causes of Homelessness? Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://homelesshub.ca/collection/homelessness-101/what-are-the-causes-of-homelessness/

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2024a, January 26). Everyone Counts 2020-2022 – Results from the Third Nationally Coordinated Point-in-Time Counts of Homelessness in Canada. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/reports-rapports/pit-counts-dp-2020-2022-results-resultats-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2024b, May 3). Solving the Housing Crisis: Canada’s Housing Plan. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/housing-logement/housing-plan-report-rapport-plan-logement-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2024c, November 29). Homelessness Data Snapshot: The National Shelter Study 2023 Update. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/reports-rapports/data-shelter-2023-donnees-refuge-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2024d, December 17). Solving the Housing Crisis: Canada’s Housing Plan. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/housing-logement/housing-plan-logement-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2025a, January 8). Shelter Capacity Report 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/reports-rapports/shelter-cap-hebergement-2023-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2025b, January 22). Homelessness data snapshot: Analysis of chronic homelessness among shelter users in Canada 2017 – 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/reports-rapports/chronic-homelessness-2017-2023-litinerance-chronique-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2025c, January 28). Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/index-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2025d, January 28). Reaching Home directives. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/directives-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2025e, February 21). About the National Housing Strategy. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/housing-logement/ptch-csd/about-strat-apropos-eng.html

- Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada. (2025f, March 19). Data analysis, reports and publications. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://housing-infrastructure.canada.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/reports-rapports/index-eng.html

- Medi, L. (2024, April 8). Canada is failing to tackle its housing and homelessness crisis, and the international community is watching – Canadian Centre for Housing Rights. Canadian Centre for Housing Rights. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://housingrightscanada.com/canada-is-failing-to-tackle-its-housing-and-homelessness-crisis-and-the-international-community-is-watching/

- O’Neill, N. (2024, November 26). Here’s how many people will be at risk of homelessness by 2030, according to this AI. CTVNews. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/article/heres-how-many-people-will-be-at-risk-of-homelessness-by-2030-according-to-this-ai/

- Statistics Canada. (2023, December 6). Homelessness: How does it happen? Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/5170-homelessness-how-does-it-happen

- Thistle, J. (2017). Indigenous Definition of Homelessness in Canada. In HomelessHub. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/COHIndigenousHomelessnessDefinition.pdf

- Tria Espinoza, F., & Randle, J. (2025, February 12). Exiting homelessness: An examination of factors contributing to regaining and maintaining housing. Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 30, 2025, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/46-28-0001/2025001/article/00002-eng.htm